The Deep Guts: Diving into ‘Orca’

By Michael Crosby

Most horror fans will recognize the title Orca (1977) almost instantly. A project uniquely born of the 1970s, Orca was the brainchild of Dino De Laurentiis, the Italian film financier behind the 1976 remake of King Kong. De Laurentiis bankrolled a number of genre offerings during his wide and storied career, most notably attempting to cash in on the “disaster film/eco-horror/summer blockbuster” template established by Jaws (1975). King Kong was his first serious attempt, and, arguably, his biggest failure. While revisionist critics enjoy painting De Laurentiis as a failure, his films did make money, and, in some cases, they made BIG money. No matter what you may think of King Kong, the truth is it scarfed up over $100 million altogether and was one of the first big-ticket films to score money exploiting ancillary markets. Kong was also one of the first films to have a novelization, puzzles, action figures, a baseball card set, posters and even a commemorative cup from McDonald’s. So, the Italian mogul had plenty in the coffers to bankroll his next attempt at stealing Jaws’ thunder, or at the least some of its audience.

De Laurentiis enlisted writers Luciano Vincenzoni and Sergio Donati with a directive: find the biggest and baddest creature in the ocean, something that could take a Great White in a fight. The writers settled on the killer whale, the Orca, and it was off to the races. The film, also produced by Vincenzoni, was directed by Michael Anderson and shot in Newfoundland before moving to Malta, which doubled for the Arctic setting of the film’s climax. Released in the summer of 1977, Orca made about $14 million from its $6 million budget and was generally considered a flop, particularly with critics who pasted the film relentlessly. It’s gained a cult following in the years since, primarily for the sumptuous photography, Ennio Morricone’s ethereal score, Richard Harris’ alternately campy-yet-grounded performance, and the fact that Bo Derek gets her leg bitten off in spectacular fashion in her feature film debut.

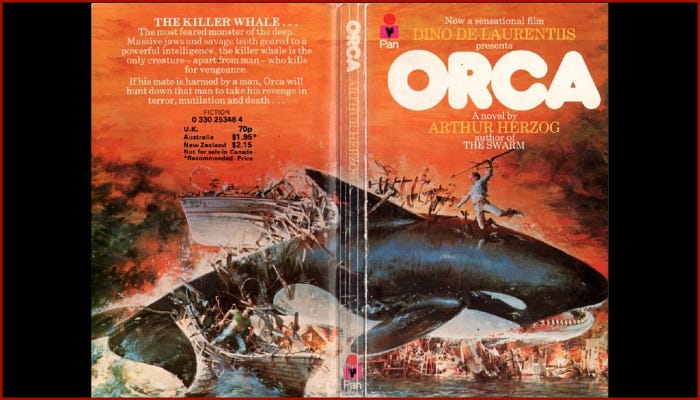

Orca wasn’t a big enough (or profitable enough) production to earn King Kong’s ancillary revenue streams, but it did produce one neat collectible: a deceptive novelization by Arthur Herzog, famous for his novel The Swarm (1974). I say “deceptive” because it’s presented as an original novel by the author, not as an adaptation of an early screenplay draft, which it clearly is. One supposes this is another example of De Laurentiis’s Jaws envy. Jaws was based on Peter Benchley’s best-selling original novel; therefore, Orca should have the same! Releasing the book only scant weeks away from the film’s premiere was also a tip-off. The Orca novel (1977) is a fascinating time-capsule in some ways. Only ever issued as a paperback first edition, the wraparound cover art features the theatrical poster artwork, and stuck smack in the middle is a full-color ad for Kent cigarettes. The most interesting differences between the novel and the final film, of course, stem from the story within.

Novelizations have changed a bit since then, but your typical novelization back in the day could result in a radically different product than what is seen on-screen, primarily because of publishing dates forcing authors to work from very early drafts of a given script so that the book is produced on-time. This can result in some wild variances between novel and film. A famous example of this is Hank Searls’s novelization of Jaws 2 which was based on an early draft of a script written by original director John Hancock and his wife Dorothy Tristan. They were then unceremoniously fired by Universal, and the script was completely rewritten by original Jaws scribe Carl Gottlieb. The Orca novelization is similar. The differences between the novel and final film suggest the novel was an adaptation based on an early draft of a script, a script that then went through rewrites by an uncredited Robert Towne (yes, THAT Robert Towne) while the novel remained the same adaptation from the earlier script. Let’s examine the similarities and differences.

The film’s basic plot and many of the set pieces remain the same as the novel. Moody, alcoholic sea Captain Jack Campbell, his younger sister Annie, her boyfriend Paul, and their first-mate Novak run the trawler Bumpo from which they earn a living by fishing and running charters. Campbell jumps at an opportunity to capture a Great White Shark for a big payday, hoping to pay off his boat and struggling marina. Traveling to Newfoundland, Campbell tracks a white shark to a cover where two divers quickly become endangered. No need for Campbell to come to the rescue, though, since a mammoth bull orca rams the shark, killing it. Campbell hints on the notion of capturing the bull instead, despite the warnings of one of the rescued divers — a zoological professor that specializes in killer whales. Campbell rebuffs her, and the attempt to capture the orca goes horribly awry as Campbell accidentally ensnares the whale’s mate, causing her to abort a stillborn fetus and then slowly die herself. The bull, overcome with rage and grief, begins tracking Campbell, hoping to force him into a fight on the water. Campbell, a troubled man but not a monster, refuses to take the bait. As the whale begins to lay waste to the small coastal town, driving away its fishing livelihood by sinking boats, blowing up the town’s fuel supplies, and generally being one ornery critter, Campbell becomes caught between his conscience and the town’s leaders who begin pressuring him by means both fair and foul to sail and lead the beast away from them. In a truly gruesome moment, Annie’s leg is bitten off. This prompts Campbell to snap and he takes the fight to the whale, who leads them steadily into Arctic waters for a final showdown.

This essential storyline is also in the novel. However, the most immediate differences are ones of tone. A vast majority of the changes from novel to film lighten the story’s tone considerably and much to the film’s benefit. The novel is very much a pulp adventure, and with that format come all sorts of racist and misogynistic throwbacks that kept me feeling as if I’d fallen down a pop-culture rabbit hole. Herzog’s Campbell isn’t very loveable. He isn’t a monster either, but he has no problem calling female characters “bitches,” hurling racist insults at the Native American guide Umilak or bedding every willing female he can find. The film makes vast improvements to the Campbell character. Richard Harris is perfect to play a loveable rogue like Campbell in the film but not so for the novel’s version of the character. In the film, Charlotte Rampling’s Rachel can plausibly (barely) see the good in Campbell. In the novel, Campbell has few if any redeeming qualities, and it’s jarring and ridiculous that she would jump into bed with him a few pages after being told: “Go to hell, bitch!”

Another significant character alteration is Jack’s younger sister, Annie. This time the changes from novel to film weaken the character. In the novel, Herzog’s Annie is a smart, verbose young woman with a take-charge air about her. In the film, both the part and the dialogue have been drastically reduced. One wonders if this was to accommodate the casting of Bo Derek, previously a model with little acting experience. Annie in the film becomes your typical damsel-in-distress who is easy on the eyes. Most of her substance is eliminated.

Many minor scenes from the novel are trimmed or eliminated completely in the final film. Again, most of these changes are for the better. In the book, the story begins with Annie forcing Campbell out of his doldrums by taking him to a Sea World-style aquarium. It is here that he takes in a killer whale show and becomes fascinated with them. The film abandons this scene in favor of introducing the orca pod that is central to the story, showing them frolicking in the ocean to Morricone’s score and, in a sense, humanizing them. The Rachel character isn’t introduced in the book until the Great White shark attack. Rampling’s Rachel in the film is introduced immediately after the whales appear. She gives a lecture on orcas that features all the announcer’s dialogue from the killer whale show that Campbell attends in the novel. In the film, Campbell attends the lecture instead, meeting Rachel right away and establishing an antagonistic — if playful — relationship.

Some more positive changes from novel to film are scenes and characters completely dropped altogether. These include two teenagers who sneak away to have sex (of course) and witness the whale’s attack on the town’s underwater fuel lines, confirming that the whale is responsible. Another is just a shameless lift from Jaws: the town’s mayor (of course) is desperate to keep the news of the whale’s attacks on South End under wraps to avoid scaring off the tourist trade (groan). It doesn’t help that the character is the most thinly drawn Snidely Whiplash type of villain. Good riddance.

Again, the differences are really a matter of tone. The novel’s characters tend to be ugly roughnecks who are crude and brutal. Towne’s rewrite appears aimed at softening this aspect while helping to humanize the whale’s motives. In the novel, not much time is spent attempting to give the whale any shadings. The film, primarily through the cinematography and the score, gives the creature a dignity and empathetic quality sorely lacking in the novel. Orca may not be the greatest film in the world, but it works, and it works partly because of the effort to give the beast a distinct personality and humanize its grief.

Still, the biggest change between the novel and the film is the previously mentioned Jack Campbell character, and again, the film is so much better for it. Little has been written about Orca’s production so it’s impossible to know for sure, but an educated guess leads me to believe that the casting of Richard Harris had a lot to do with this improvement. Harris has far too much natural roguish charm to play such a one-note shallow character as depicted in the novel. In the novel, Campbell’s fight with the whale doesn’t have much depth, and Campbell himself is a reactionary character, acting only when forced by the town or compelled by his own needs. The film, and thus Harris, gives the character far more depth and eventually redeems himself by introducing a much needed, if somewhat clichéd, backstory that connects him emotionally with the orca’s rage and plight. Campbell wasn’t always a bastard but a happily married man whose wife and child were killed by a drunk driver. As he notes to Rachel, regarding the whale, “I was his drunk driver, you see.” It’s a frail, human moment, and it allows Rachel to abandon her combative stance, embracing Campbell and his humanity. No such scene appears in the novel, leaving Campbell a stock character and his relationships with both Rachel and whale wholly unbelievable.

It’s for these reasons that the film, while not a definitive success, still resonates with many fans to this day, while the novel remains mostly forgotten. 🩸

About

Michael Crosby was a contributing writer for Manor Vellum. He passed away on December 5, 2020, and we miss him dearly. His articles remain on this site in his honor.

Follow MANOR on Bluesky, Facebook, Instagram, Pinterest, Threads, TikTok, X, YouTube, and other sites via Linktree.

© 2020 Manor Entertainment LLC